Why are there these major differences in the way that easterners and westerners tend to view the world?

Richard Nisbett and his team offer an explanation. And its roots take us on a journey back to Ancient China during the Han dynasty and to Ancient Athens. Even today, most of the east is a kind of synthesis of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism.

Different countries, of course, have a different mixture of these three, and to different intensities. These three teachers are collectively referred to as either “the three teachings” or “the three vinegar tasters”: Laozi, Confucius, and the Buddha Siddhartha Gautama.

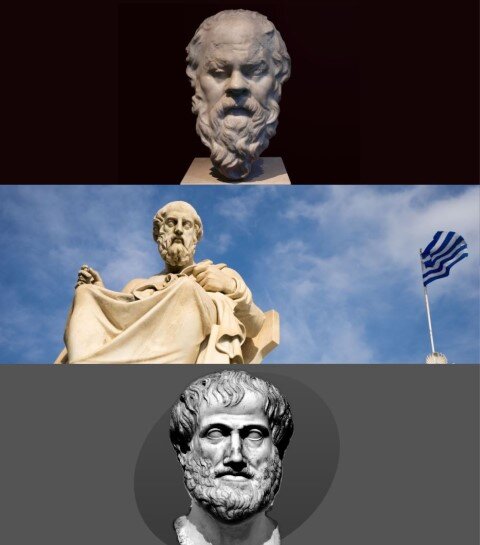

All three of them come from the warring states period, right around the sixth to fifth century BCE, so about 2,600 - 2,500 years ago. Now, amazingly, in the west, at the same time, we find three figures who’ve shaped much of western culture. Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle - referred to collectively as “The Big Three”

What was in the water at this time that allowed these 6 great-grandfathers of eastern and western culture to all live within 150 years of each other? Richard Nisbett in “Geography of Thought” lays out a very thorough argument about the origins of the culture and mindset of the east and west.

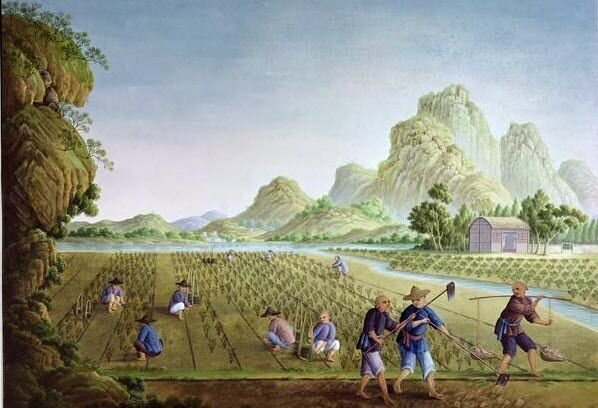

Ancient Chinese geography and agriculture

First, we need to consider the geography of ancient China during the Han dynasty 2600 years ago. There were large, vast, open plains with rivers flowing through them. Food production relied primarily on rice cultivation. Now, in order to cultivate wet rice, it's extremely beneficial to have big groups of people all working in little pieces of the plot. This required large-scale cooperation. It was only possible to cooperate on such large scales because of how vast the rolling hills were on which they worked.

Ancient Greek Geograpahy and Agriculture

Nisbett compares this to the agriculture of Athens, the bedrock of western culture. Instead of wide open plains, the geography of Athens is mostly mountains and the sea. Because of this, the food production was not on large-scale rice production or large-scale farms, or large-scale anything. Mostly the food production was through hunting, herding, fishing, and through small-scale olive and green production. None of these require large-scale cooperation. You can be an individual olive or grain farmer. You can be an individual hunter, an individual herder, or an individual fisher. So Ancient Athenians didn't require the kind of communal living that we tend to associate with the East.

Ancient chinese’s homogeneity and ancient greek’s heterogeneity

ANCIENT CHINESE’S HOMOGENEITY

The other important point that Nisbett focuses on is that the Han dynasty was incredibly homogeneous. At that time, there were more than 95% Han Chinese. This means that people would go an entire lifetime without ever interacting with someone who wasn't Han Chinese. Because of this, they had little contact with radically different world views.

They were interacting almost exclusively with people who spoke the same language, wore the same clothes, ate the same food, had the same values, etc. They had the same wedding ceremonies and the same kinds of funerals. They held the same beliefs about morals and the afterlife. All was basically the same. Because of this, people weren't really debating. Everyone believed mostly the same thing, so there was little need for debate. The incentive then for philosophical inquiry wasn’t, as compared to the west, to find the “Truth”. It was to maintain harmonious social relationships.

Nisbett argues that because of the wet rice cultivation and working in these large-scale farms, it was incredibly important, even necessary, that people have really harmonious living, and that we put the group ahead of the individual. We can compare this to the heterogeneity of the west.

ancient greek’s heterogeneity

Now, in contrast, at the time Ancient Athens was incredibly heterogeneous. And its primary economy was maritime, focused on trading with other countries and nation-states. Tradesmen would get on a boat and arrive in a different land, different city, different country. A place with very different customs. They were frequently interacting with radically different ideas, people who had different gods, people who ate different foods and prepared it in different ways, who wore different clothing, spoke a different language, who had different value sets, who had different expectations about what polite is, how manners are supposed to be.

With so many different and conflicting ideas, which one is the right one? This is why the Ancient Athenians relied heavily on debate. To find the Truth, the capital-T Truth. They’d look at different cultures and say “Okay, well whose god is the best? Whose food is the best? Whose way of managing the economy, whose way of arranging the government is the best?”

Abstractions in ancient greece

This heterogeneity also caused something that was very uniquely western according to Nisbett: the ability to abstract. These frequent interactions with diverse, conflicting cultures forced abstraction for survival in the maritime Greeks. On their expedition, interacting with another culture, one might say, “I believe in the god Zeus, but you believe in the god Zarathustra. Even though your god is different from my god, maybe we can say that there's something similar about our gods. We can invent a new word - let's call it “godliness,” an abstract principle describing the characteristics of a God. One which can apply to all gods. It doesn't have to be one particular god. It can be this abstracted idea.

In fact, one of the most famous philosophical theories coming out of this time is Plato's "Theory of the Forms.” Plato said, basically, “yeah there's this chair and there's that chair and there's that chair. But there is the Realm of the Forms where the True Chair exists. And all of these chairs that we see with our eyes, these are merely manifestations, replications, reflections, shadows of the one True Chair.

This is a fundamental ability, Nisbett's and his team assert, that so substantially distinguishes the West from the East. Now there’s no judgment here; the ability to abstract is not necessarily a good thing, but it does lead to some extreme differences in culture.

Athenians developed the ability to add the suffix “-ness” to the end of basically any word. They could change any adjective to a noun by adding “-ness”. The green of limes and the green of olives can just become “green-ness” and eventually this becomes just “green”.

With abstractions, we can look at one kind action that a person does, and one kind action that another person does, and we can abstract the commonalities. And we can call these actions Kingliness or Godliness.

In Ancient Eastern culture, according to Nisbett, these kinds of abstract words did not exist. He writes: “There is the whiteness of the horse or the whiteness of the snow in ancient Chinese…, but not whiteness as an abstract, detachable concept that can be applied to almost anything.”