Polyamory

Real Talk Philosophy Artwork

Introductory Discussion Questions

What is monogamy? What is polyamory?

Have you explored non-monogamy? Where do you fall on the monogamy/polyamory spectrum?

Have you ever experienced jealousy? What was that experience like for you? Where does jealousy come from?

Do you believe in “the one?” Is it possible to simultaneously be in love with more than one person?

Are there benefits of romantic and sexual exclusivity?

Would you feel differently about your partner sharing sex/romance with someone who is not your sex?

What is Polyamory?

Etymology of polyamory

The word polyamory is a mix of both greek and latin roots. From the Greek, poly, meaning “many” and the Latin, amor, meaning “love”.

Definition of polyamory

Polyamory can be defined as the practice of engaging in multiple sexual or romantic relationships with all partners’ full knowledge and consent. This can be practiced all together, or this can be practiced separately. This can be romantic or this can be sexual. Aromantic, asexual. Straight, gay, bisexual. The most important element is the full knowledge and consent of all partners involved.

The term ethical non-monogamy is used interchangeably with the term polyamory. These practices come in many shapes and sizes. But before examining all the ways polyamory can be practiced, it’s important that we first distinguish polyamory from what it is not.

Of course, polyamory is not monogamy. The definition of monogamy, particularly in non-human animals, is more complicated than you’d imagine. We’ll tackle that soon. Monogamy is the practice of engaging in romantic and sexual activity exclusively with one other person.

Polyamory is also not cheating. As per its definition, polyamory is practiced with all partners’ full knowledge and consent. In gameplay, cheating is defined as breaking the rules. In polyamory, you can have sex and romance with people outside your primary partnership without breaking the rules. This is because you get to define your own rules; it’s a “designer relationship.” Now, cheating can still exist in a polyamorous relationship if an established rule is broken.

Polyamory is often conflated with polygamy. Polygamy is the practice of having multiple spouses. Etymologically it technically refers to reproducing with multiple people. In contrast, polyamory does not require marriage and does not require reproduction. Polygamy is illegal in most countries and comes in two distinct flavors: Polygyny, the practice of having multiple wives; and polyandry, the practice of having multiple husbands.

Swinging is the practice of two or more couples sharing a sexual experience together and trading partners. In previous decades, before the term polyamory existed, many couples practiced swinging, or partner swapping. Swinging can be considered under the umbrella of polyamory. Swinging usually does not make room for long-term romantic relationships, but only physical relationships, and the experiences are limited to those where all partners participate, rather than either partner engaging in a solo experience.

In an open relationship, two primary partners agree that one or both partners are allowed to have sex with people outside the primary relationship. Polyamory distinguishes itself from open relationships by, as is expressed by the root-word, amor, not only allowing sex outside the primary partnership but uniquely allows for multiple, loving, romantic relationships. Polyamory is also not the same as open relationships, but, like swinging, open relationships are considered to be under the umbrella of polyamory.

In fact, polyamory doesn’t necessarily require the existence of a primary partnership at all. This is called solo poly. Now, solo poly is distinct from merely “sleeping around” as, again, this is practiced with every partner’s full knowledge and consent.

One misconception about polyamory is that it does not involve long-term commitment or fidelity. But there are many committed, exclusive, long-term polyamorous relationships. Instead of the exclusive relationship being between two partners, it exists between 3, called a polyfidelity triad, or 4, called a polyfidelity quad. And these last decades. But most polyamorists do not find themselves in tidy, exclusive bonds, but instead in a complex web connecting many people, engaged in various sorts of complex relationship dynamics… primary partners, solo polyamorists, co-parents, asexual romantic partnerships, and more.

Who Practices Polyamory?

These data were collected by the Open Source Psychometrics Project in 2015, which surveyed 4800 people in the United States. Keep in mind, these data were collected from visitors to their website, people who are interested in psychology and from the English-speaking world, and this likely skews the numbers, but these are the best we’ve got for now.

Polyamory Interest Overall

As of 2015, about 60% of people self-reported that they were not polyamorous, had never been polyamorous, and were not interested in exploring it. Nearly 8% of people self-reported that they had been polyamory in the past, but were no longer practicing. More than 25% of people indicated that they were not polyamorous, but were interested in exploring it and just over 7% of people indicated that they were currently polyamorous. There have been several other studies researching the prevalence of polyamory with numbers more or less reflecting these.

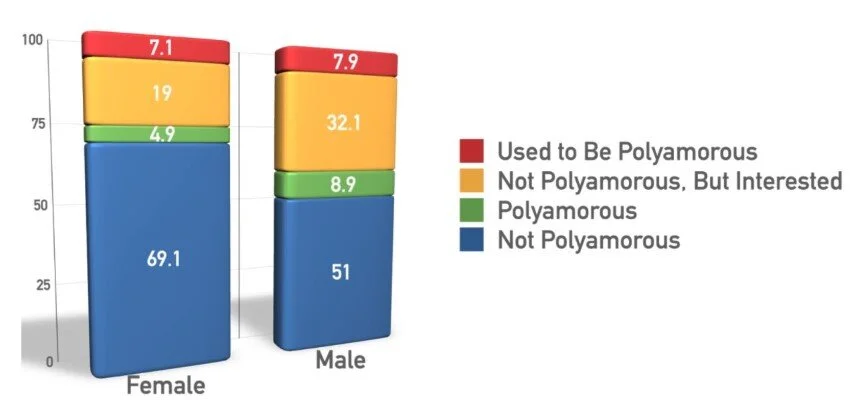

Polyamory Interest by Sex

If we break down the numbers by sex, we find many more males are interested in polyamory, and about twice the number of men are currently practicing polyamory. This aligns with other reports indicating that polyamorous triad relationships are predominantly between one woman and two men.

Polyamory Interest by Race

There also isn’t much correlation between polyamory and race. Though it appears that a slightly larger percentage of black people practice polyamory in the United States, followed by Hispanics, Asians, then whites. Perhaps there is a correlation between being a minority and not ascribing to traditional marriage roles.

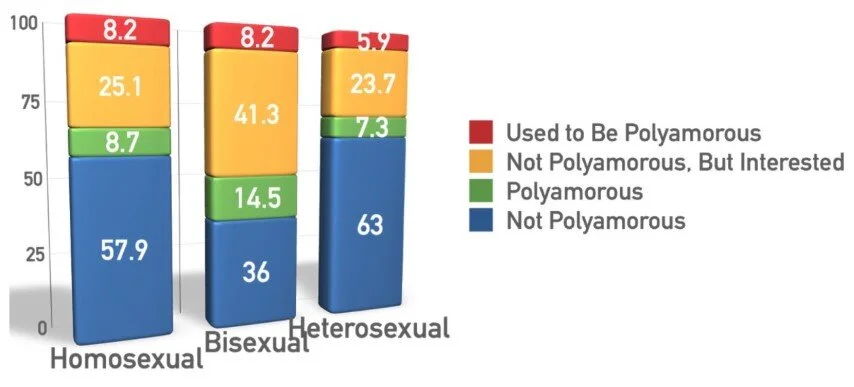

Polyamory Interest by Sexual Orientation

There is a strong correlation between sexual orientation and polyamory practice. Bisexuals practice polyamory at a rate nearly double that of heterosexuals, and 2/3 greater than that of homosexuals. There’s also much greater interest in polyamory amongst bisexuals. Perhaps you can come up with some ideas of why this might be. Perhaps non-normative sexual orientation predicts a preference for and comfort with non-normative relationship dynamics, or perhaps polyamory is the only relationship structure wherein a bisexual can have both their sexual attractions met simultaneously.

Now, these numbers are likely to change in the coming years as the acceptance of polyamory increases, and right now around the world, we find a correlation between women entering the workforce and rise in the rates of divorce and the prevalence of polyamory.

Best Reasons to Practice Polyamory

The most obvious benefit of polyamory is the opportunity to develop deep, intimate, romantic, and sexual relationships with multiple people. To not have your capacity for love stifled by a partner, and not to stifle a partner’s capacity for love.

There’s also NRE, or New Relationship Energy. Do you remember the feeling the last time you fell in love? There may be no greater feeling in the world. But conventional relationship dynamics would only allow that feeling once in a lifetime. In contrast, polyamorous relationships make room for this feeling again, and again, and again.

Polyamorous relationships allow our needs satisfied by multiple people. People usually have several friends to satisfy their diverse needs. One friend to go rock climbing with, another friend to go dancing with. But in romantic relationships, people tend to presume that one person will able to satisfy all of their complex needs. But this expectation is almost never met.

Polyamory relationships allow our emotional, sexual, and practical needs to be filled by multiple people. Practical needs like grocery shopping, cleaning the house, sharing multiple incomes, and even raising children together.

Many couples report that their primary relationship has been strengthened by practicing polyamory. In order for a polyamorous dynamic to be successful, it’s necessary for both partners to communicate clearly about their desires, fears, insecurities, boundaries, and needs. In a way that few monogamous partners are ever forced to. By navigating these incredible choppy waters, polyamorous couples discover their ability to approach any other challenging situation with nonjudgmental communication, compassion, patience, respect, and love.

Arguing against polyamory, many proponents of monogamy point to the jealousy that arises when seeing our partner engaged in a sexual or romantic relationship with another person. But this might not be a very good argument. If you were to imagine for a moment one child playing with a toy train, and a second child joins in. And the first child screams, “No! This is my toy train! Mine!”

Most of us would look at this situation and attempt to gently teach the child to share. This highlights two important issues.

1) We clearly value sharing as a society. So much so, that when children are unable to share, psychologists consider this to be a development flaw.

2) we clearly believe and have demonstrated, that even if a person is naturally possessive, they’re able to be taught to share. And will likely eventually learn to really enjoy sharing.

There’s a simple argument against this though - and that is that humans are not trains. And that our attachment to them can not be compared. Fair enough.

In response to feelings of jealousy that often arise in polyamorous relationships, polyamorists invented a new word - compersion, which, as defined by Franklin Veaux, author of More than Two: A practical guide to ethical polyamory, is “A feeling of joy when a partner invests in and takes pleasure from another romantic or sexual relationship… the opposite of ‘jealousy’ …a positive emotional reaction to a lover’s other relationship.”

But perhaps the most convincing argument for polyamory is that its alternative appears to be failing. In the USA, more than 1/2 of marriages end in divorce and it has been reported that 20-40% of these divorces were caused by infidelity. Imagine how many marriages could have been saved, how many families would not have been disrupted by the turbulence of divorce, and how many children would not be raised by single parents if couples just agreed to open up the relationship. Nearly half of all married women, and more than half of all married report having cheated on their spouse. So, although many of us parade our support of monogamy, the reality is far different.

Discussion Questions

Why are bisexuals most likely to practice polyamory?

Why is sexual non-exclusivity a dealbreaker for most couples? Are there other activities you feel must be exclusive? (holding hands, playing chess, etc.)

Is monogamy natural? Is there an evolutionary advantage?

Is polyamory the symptom of a neurological disorder? Is polyamory a sexual orientation like homosexuality or heterosexuality?

Have you ever cheated on a partner?

Is sexual and romantic exclusivity necessary for deep, committed, long-term loving relationships?

Are you more triggered by the thought of your partner romantically or sexually involved with someone else?

Would easterners or westerners be more likely to practice polyamory?

Is Monogamy or Polyamory More Natural?

Proponents of monogamy argue that polyamory is clearly unnatural, otherwise we wouldn’t experience such intense feelings of jealousy, possession, fear, inferiority, insecurity. As of 2015, about 60% of people self-reported that they were not polyamorous, had never been polyamorous, and were not interested in exploring it. They also look to other animals who practice monogamy. You may have heard that about 90% of birds are monogamous, which is technically true, but what’s meant by monogamy when applied to non-human animals by biologists is quite different than what the average person means.

Animal researchers distinguish between two, sometimes three different forms of monogamy: There's sexual monogamy, which is what most of us usually mean when we use the word monogamy, referring to the practice of exclusive sexual relationships. But this is extremely, extremely rare in non-human animals. There’s also social monogamy. Which refers to exclusively living with one other partner and cooperating in search of food, finding shelter, and caring for the young. In addition, some biologists also make a distinction between sexual monogamy and genetic monogamy, which is the practice of reproducing exclusively with one partner but still engaging in sexual and social relationships outside this primary bond. When biologists use the term monogamy to describe the habits of non-human animals, they are generally referring exclusively to social monogamy, not sexual or genetic monogamy. Although, this may only be a distinction applied to humans, as it’s unclear whether or not any non-human animals exhibit any kind of contraceptive behavior. For instance, Gibbons usually keep the same mate for life but are not sexually monogamous. Complicating things further, unless explicitly stated, biologists are usually not referring to lifelong exclusivity with a single partner, but rather to the practice of a succession of exclusive relationships, or Serial Monogamy. Some argue that humans are serial monogamists by nature, but even this claim is rife with contention. Black vultures are sexually monogamous, but only while their offspring need care from both parents. The same goes for Emperor Penguins. Though they are sexually monogamous for a time, Approximately 85% of Emperor penguins find a new partner every breeding season. The definition of monogamy, when applied to non-human animals generally does not refer to strict, 100% monogamy, but instead to mostly monogamous couplings. A dynamic playfully referred to as monogamish.

Now, there are some examples of non-human animals who practice lifelong, strict, sexual monogamy, for instance, hornbills, Azara's night monkey, and male prairie voles. Male Prairie Voles are strictly sexually monogamous for a lifetime. In fact, the male prairie vole is known to attack any other female that approaches him. Researchers have indicated that this behavior is linked to a hormone called vasopressin, which is released when the male prairie vole mates or cares for his young. To test the effect of vasopressin, researchers have injected vasopressin receptors into another, more promiscuous species of vole and as anticipated, following the introduction of this hormone, promiscuous voles were seen to exhibit strict monogamy. Now, to bring this back to humans, vasopressin receptors can be found in the human brain a well. And they vary from person to person. Perhaps this is why some people prefer monogamy, and others don’t. But there haven’t yet been any reliable studies observing the correlation between vasopressin levels in humans, and preferences for monogamy.

Now, on the other side of the spectrum, we find bonobos and chimpanzees. The closest genetic relatives of human beings. Bonobos and Chimps are non-monogamous. They mate 1-4x an hour, with up to 12 partners a day. Researchers indicate that they have sex not just to reproduce, but to bond. They have sex to say hello, to say goodbye, when they’re stressed out. This is why, like humans, they face each other during sex, unlike almost every other mammal. Like humans, chimps and bonobos also exhibit Female Copulatory Vocalization, that is, moaning. Moaning almost exclusively found in primates that engage in sperm competition. It’s suggested that the moan is an invitation for other males to compete for the opportunity to mate with the female and that human females moan for the same reason. In fact, it’s presumed that the head of the human penis is shaped so as to evacuate the sperm of competing males.

Many advocates of polyamory argue that human beings, like chimps and bonobos, are biologically non-monogamous, and were up until the agricultural revolution, when they say that the concept of private property was first invented. The agricultural revolution took place 12,000 years ago. So this is only about 6% of humans’ total time on earth. But there certainly is some debate around this issue, as there is very little evidence and lots of speculation from either side.

There are some human groups that still practice non-monogamy today. Like the Mosuo, an ethnic group from Southwestern China where everyone is completely sexually autonomous. Children are raised not by the father, but by the mother’s family.

Also, for the Bari of Venezuela, it is customary for women to sleep with multiple men with the belief that that the child will inherit the qualities of each. So, if the mother wants a child who is musical and brave, she can sleep with a musician and a hunter. Every man who sleeps with the mother is considered the child’s father who jointly helps raise the child.

Franklin Veaux, author of More Than Two: A Practical Guide to Ethical Polyamory, argues that humans are naturally polyamorous, naturally monogamous, and naturally asexual. Humans are remarkably variable compared to any other animal, and therefore comparisons really can’t be made. He remarks that humans are naturally left-handed, right-handed, ambidextrous, black-haired, brown-haired, bald, polyamorous, monogamous, asexual, aromantic, and that attempting to make claims about how we should or shouldn’t act is fruitless. We should instead be investigating our own intuitions and desires.

All of these claims fall under the domain of the Appeal to Nature Fallacy, a logical fallacy in which an attempt is made to argue that a thing is good because it is 'natural’, or bad because it is ‘unnatural’. Just because something is natural doesn’t make it right. There are many things that are natural such as murder, physical, violence, and rape. Making presumptions about what is natural and what isn’t has been used to justify the unequal treatment of gay people, people of color, women, and others for centuries. So this entire argument about which is more “natural” might be best to ignore. But there are many benefits and detriments, and ethical arguments for and against both polyamory and monogamy.

Best Reasons Not to Practice Polyamory

First, polyamory is just wrong. It’s either multi-amory or poly-philia, but mixing greek and latin roots is just wrong.

Many claim that polyamory is a great idea in theory, but just not practical. It paints an idyllic picture of human psychology wherein any challenge can be overcome by communication, vulnerability, and rationality. But human beings aren’t rational. We are deeply complex, messy, and flawed. Polyamory doesn’t take into account the reality of feelings of jealousy, feelings of possession, feelings of insecurity, or fear of abandonment that naturally arises, the flip side of experiencing so much love is an inordinate amount of heartache and heartbreak.

Having a greater number of partners increases the overall amount of emotional support a person needs to provide. Sometimes people just go through bouts of depression. Sometimes lasting months or years. Without a firm commitment, and the opportunity to explore other people, do you believe your partner will stick through this time with you?

They may say that love is unlimited, but time isn’t. Many people can’t find time to adequately support one partner, let alone 3 or 4. This scarcity of time sometimes causes difficult choices to be made. One could envision a polyamorous utopia wherein all partners are treated with equal time and affection. Where all your lovers will be invited to your sister’s wedding. But this is almost never the case. A hierarchy, a pecking order is almost always established. For a primary partner to be downgraded from their exclusive seat of supreme importance in the mind and heart of their lover can be devastating.

Even if all of this feels worth it to you, finding partners can be extremely challenging. Potential romantic partners often get scared off by the word ‘polyamory’ assuming it will invariably lead to heartbreak. And once you do find partners, the expectation that your partners will get along swimmingly is misguided. Sometimes that unicorn polycule is achieved where all partners involved love one another, but this is extremely rare. Now, it’s presumed that all of this potential for jealousy, heartache, and fear can be remedied through conversation. But this often leads to exhaustive, tiring communication tearing apart the nuances of each action and feeling. This leaves many polyamorists longing for the days of having one simple, unshakable rule. Don’t sleep with other people.

Even if you do find the right partners and find the communication skills to navigate them smoothly and everyone involved gets along, coming out to your friends and family about your chosen relationship dynamic can lead to judgment, criticism, name-calling, and abandonment, comparable to coming out as gay. How would your family respond if you brought home 2 lovers for New Year’s dinner?

Once the relationship gets more serious, the children must be considered. It can be extremely beneficial to be raised by several parental figures. But if one parental figure were to leave, and there wasn’t the institution of marriage stopping them, it can be extremely devastating for the child.

Now, to the argument that polyamory is somehow more natural than monogamy, some pro-monogamists say, “yeah, polyamory is more natural, but there are many things that exist in the natural world that we do not value as human beings.” Murder is natural. Physical violence is natural. Rape is natural. But as human beings, we've collectively decided that there are some parts of our nature that are extremely beneficial to transcend. Maybe polyamory is natural. But maybe it’s important that we transcend this piece of our nature. Now, why might it be beneficial?

Maybe people have the presumption that in a world absent of monogamy, there would be more love for everyone. But if we look at the animal kingdom, this isn’t actually the case. More than 90% of mammals practice not only polyamory, but polygyny, that is - one male with multiple females. And as a result, we see what’s known as the Pareto Distribution or the 80-20 rule. That is, in the animal kingdom about 80% of females are partnered with only about 20% of males. It’s been argued thoroughly that the primary reason human beings have so successfully dominated the planet is our unique ability to cooperate in such large numbers. But if only 20% of males have female sexual partners, there would likely be an unprecedented amount of fighting and competition within the species. Our ability to collaborate would crumble. So, a remedy for this fighting would be to ensure that every male has one female.

The last major argument made against polyamory here is around the concept of sacrifice. Ancient cultures and religious stories uphold the value of sacrifice, like the story of Abraham and Isaac. According to the story, though he and his wife Sarah prayed incessantly for a child, it wasn’t until Abraham’s 100th year that Sarah conceived. Then, after his birth, Abraham was instructed by God to sacrifice his son, Isaac. After tying his son to an altar, Abraham pulled out his knife ready to slit his son’s throat, and at the last second, an angel came to stop him. Even if you believe these stories aren’t true, perhaps it’s still worth considering the ancient wisdom they might hold. Why was this story considered to be of such importance that our ancestors passed it along for thousands of years, first by words of mouth, then through text, then enshrining it in the institution of religion? But what exactly is the moral here? That we should have blind faith in God and if we’re schizophrenic and hear voices that tell us to kill someone we should listen? Or maybe this is a story about sacrifice.

We don’t really have many practices of sacrifice today. We don’t sacrifice our goats or our crops to God. When we do make sacrifices, they’re usually for some practical means - giving up alcohol or desserts. But is there an affirmative value of sacrifice? It’s not just anything we should be giving up. Isaac was the thing Abraham wanted and loved most in the world and this is what God ordered him to sacrifice to affirm his devotion. Maybe it’s because we love romance, new relationship energy, and sex so much, that this is exactly what we should sacrifice to affirm our devotion to our partner, to be all-in.

Discussion Questions

If humans lived forever, how long would the ideal relationship last?

Should we allow children to be raised in polyamorous households?

Why have governments, institutions, religions, etc. conventionally promoted monogamy?

Which is more intimate: sex or kissing?

How would your family feel if you came to dinner with multiple partners? How would you remedy this?

Are polyamorous relationships less deep than monogamous relationships?

Do you have enough time for one partner? For several?

Is there any benefit to sacrifice?

If polyamory were normalized, would it result in mostly polygyny or polyandry?